AI Hype, Model Collapse, and the Dead Internet

I've been watching AI models dream about my French Bulldog lately. The images are charming at first: stumpy legs, bat ears, that distinctive underbite. But look closer. The church steeple behind him has melted. The cobblestones have become scales. And sometimes, in the background, there's a figure that might be human, might be furniture, might be nothing at all.

This aesthetic glitch mirrors something far more troubling happening inside the models themselves. Researchers at Oxford and Cambridge found that when AI models train on AI-generated content, they don't just get worse. They collapse.1 In one striking example, a model trained iteratively on its own outputs devolved from coherent text about medieval architecture into rambling nonsense about "jack-tailed rabbits" and "yellow-skinned" creatures that existed nowhere but in its own degrading probability distributions.

Everyone's asking whether AI is a bubble. Are we in another dot-com crash? Will the chips go dark, the data centres empty, the stock prices crater?

They're asking the wrong question.

The infrastructure might hold. The minds and the data might not.

The Bull Case (Steel-Manned)

Let's be fair to the optimists. They have a stronger case than the tulip-fever crowd might like.

There are the new kids on the block—the OpenAIs and the Anthropics of the world, burning through cash like there's no tomorrow, with neither a whiff of a profit nor a business plan in sight. But let's set those aside for a moment.

The world still turns on the incumbent "big five" with pre-existing businesses that produce real revenue streams. In October 2025, Fed Chair Jerome Powell drew a sharp line between this boom and the dot-com era. Unlike those companies, he noted, the current crop of AI leaders "actually have earnings."2 Microsoft, Alphabet, Amazon, and Meta posted a combined $78 billion in capital expenditure in Q3 2025 alone, and Apple isn't going away any time soon.

This isn't Pets.com with a talking sock puppet. It's real kit in real buildings, drawing real power.

The International Energy Agency estimates that global electricity consumption from data centres reached approximately 415 terawatt-hours in 2024—about 1.5% of global consumption, having grown at 12% annually over the previous five years.3 That demand shows no sign of slackening. Janus Henderson's technology team projects that "demand for compute power will continue to outstrip supply" through 2026 and 2027.4 Unlike the dark fibre of the 1990s telecom bust, there are no warehouses of idle chips gathering dust.

Then there's the Jevons paradox, a counterintuitive economic principle from 1865: when a technology becomes more efficient, people don't use less of it. They use more. When DeepSeek demonstrated that powerful AI models could be developed at a fraction of the assumed cost, markets briefly panicked. Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella responded by invoking exactly this logic: "Jevons paradox strikes again! As AI gets more efficient and accessible, we will see its use skyrocket, turning it into a commodity we just can't get enough of."5 Just as more efficient steam engines led to more coal consumption, not less, cheaper AI processing may simply mean more AI deployed in more places.

The bulls aren't deluded. They're answering a real question about financial viability.

But they're answering the wrong question.

The First Hidden Cost: Model Collapse

Here's what the infrastructure bulls aren't pricing in.

In July 2024, Nature published a paper that should have caused more alarm than it did. Ilia Shumailov and colleagues demonstrated that "indiscriminate use of model-generated content in training causes irreversible defects in the resulting models, in which tails of the original content distribution disappear."1

In plain language: when AI eats AI, it forgets how to think about anything unusual. The "tails" are the rare and interesting cases—the exceptions, the edge cases, the weird and wonderful corners of human expression. Those vanish first. What remains is an increasingly bland statistical average.

The technical community has developed a mordant vocabulary for this. Model collapse. AI inbreeding. Habsburg AI (after the royal dynasty that famously bred itself into genetic oblivion). Model autophagy disorder, or MAD.6 The nicknames are darkly comic, but the mathematics isn't.

A team from NYU and Meta (Kempe, Feng, Dohmatob) provided formal proof at ICML 2024 that this collapse follows predictable patterns. As more synthetic data enters training sets, the traditional "scaling laws"—the observation that bigger models trained on more data reliably produce better results—begin to fracture. Accumulating fresh human-generated data alongside synthetic data can slow the degradation, but it cannot eliminate it.7

This matters because the entire AI industry rests on an assumption: that you can keep feeding more data to bigger models and get proportionally smarter outputs. But what happens when the web—the primary source of that data—becomes saturated with AI-generated content?

The bulls ask: "Will AI keep getting better?" But they assume clean training data, an inexhaustible substrate of human thought and creativity. What if that substrate is already contaminated? What if the golden age is eating itself?

The Second Hidden Cost: The Dead Internet

Here's where it gets properly grim.

In 2023, the cybersecurity firm Imperva reported that 49.6% of all internet traffic came from non-human sources.8 By 2024, that figure had crossed the halfway line: 51% of web traffic was automated, the first time in a decade that bots had outnumbered humans online.9 Nearly four in ten of those bots were malicious.

But bots are only half the story. In April 2025, the analytics company Ahrefs analysed 900,000 newly published English-language web pages. The finding: 74.2% contained AI-generated content.10 Not outright slop—the industry's unkind term for low-quality AI output—necessarily. Only 2.5% were "pure AI," untouched by human hands. But the contamination was pervasive, the fingerprints everywhere.

This matters for model collapse, obviously. But it also matters for something harder to quantify: the texture of online life.

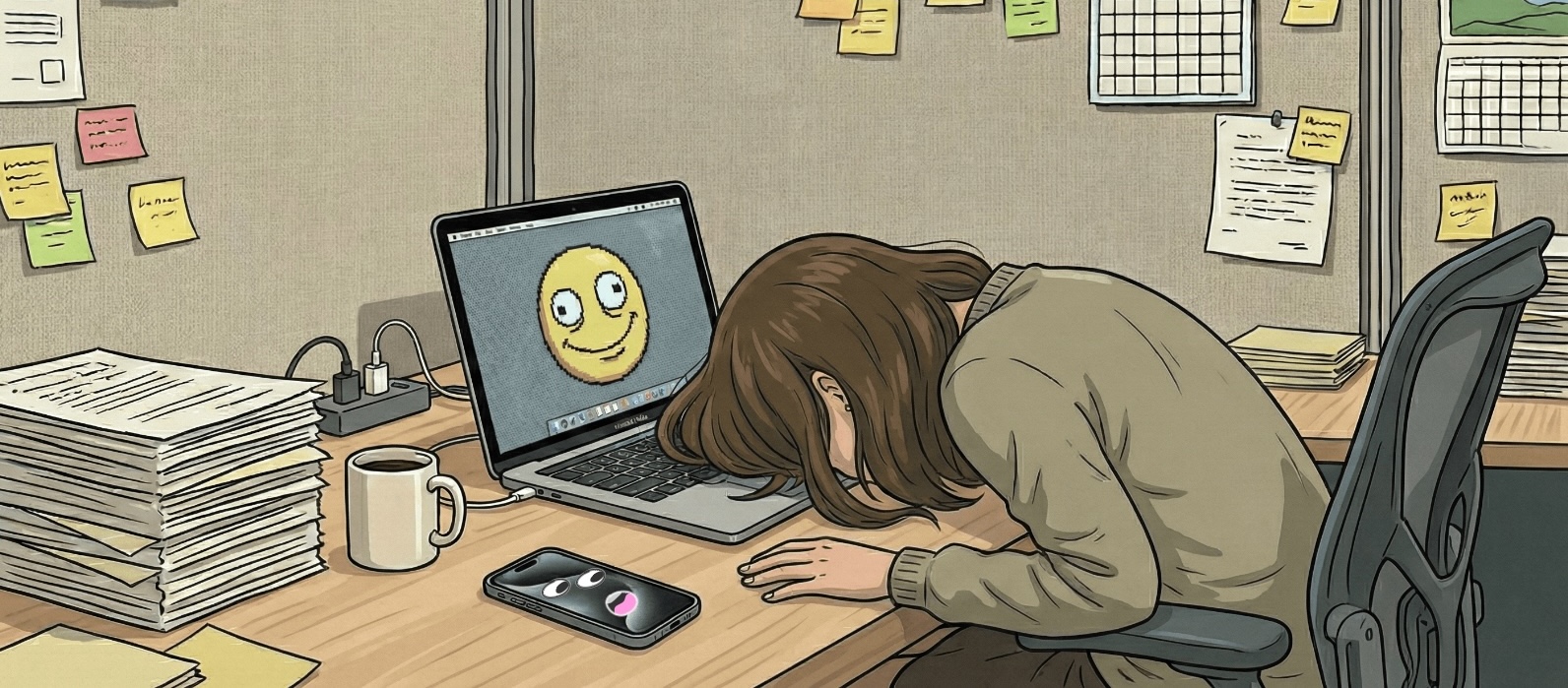

Sam Altman, the man who brought ChatGPT to the world, confessed in September 2025 that he could no longer tell humans from bots. Reading a Reddit thread praising his own company's product, he wrote: "I assume it's all fake/bots, even though in this case I know the growth is really strong and the trend here is real."11 Real people, he noted, had picked up distinctive verbal tics from chatbots. The net effect? "AI Twitter/AI Reddit feels very fake in a way it really didn't a year or two ago."

A month later, Reddit's co-founder Alexis Ohanian went further. "So much of the internet is now just dead," he told the TBPN podcast. "Whether it's botted, whether it's quasi-AI, LinkedIn slop. Having proof of life, like live viewers and live content, is really fucking valuable to hold attention."12

Remember the "dead internet theory"? It started as a 2021 conspiracy post on an obscure forum, claiming that bots and algorithms had already supplanted human activity online. Now the men who built the platforms are citing it with straight faces.

Google, of course, had already done a fine job of reshaping the modern web into a sludge of search-engine-optimized animal feed—pages written not for humans but for algorithms. AI has accelerated the process and created a feedback loop: slop trains models, models produce slop, slop floods the web, and the next generation of models trains on a substrate increasingly indistinguishable from noise.

The bulls ask: "Will AI infrastructure hold?" But infrastructure isn't the problem. The well is poisoned.

The Third Hidden Cost: Cognitive Atrophy

In 2000, Eleanor Maguire and colleagues at University College London published a study in PNAS that became a touchstone for neuroplasticity research. They scanned the brains of licensed London taxi drivers—the ones who spend years memorizing "The Knowledge," committing to memory some 25,000 streets and the complex routes between them. The result: their posterior hippocampi, the brain region associated with spatial memory, were significantly larger than those of matched controls. The size correlated with years of experience.13

The brain, it turned out, reshapes itself around the demands placed upon it. Use it, and it grows. What happens when you stop?

Subsequent research suggested the inverse. GPS users, freed from the cognitive burden of wayfinding, showed reduced grey matter in navigation-related brain regions. The skill atrophied because the struggle disappeared.

This principle extends beyond navigation. In August 2025, The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology published a study that should alarm anyone celebrating AI-assisted medicine. Researchers followed endoscopists at four Polish clinics who had been using AI tools to detect precancerous polyps during colonoscopies. When the AI assistance was withdrawn, their performance had degraded. They had become, in the study's words, "less motivated, less focused, and less responsible when making cognitive decisions without AI assistance."14

Six months of convenience. Measurable skill loss.

This isn't surprising if you've read the foundational psychology literature. Christof van Nimwegen at Utrecht University showed in 2008 that software assistance during puzzle-solving tasks led to less planful behaviour. When the assistance was removed, participants floundered, clicking aimlessly where they had previously strategised.15

Or consider what psychologists call the "generation effect": information you generate yourself, through effort, is retained far better than information passively received.16 The struggle is the learning. Remove the struggle, and you remove the mechanism by which knowledge consolidates.

Vygotsky called it the development of inner speech: thinking as internalized dialogue, shaped by the effort of articulation.17 When you let an AI write your first draft, you're not just saving time. You're outsourcing the cognitive process by which you would have understood what you were trying to say.

The infrastructure bulls don't factor this in. They model compute costs, energy demand, capital expenditure. They don't model what happens to the human capital—the skills, the knowledge, the capacity for independent thought—when AI handles the hard parts.

Short-term convenience. Long-term erosion.

The Energy Problem (Context, Not Core)

At this point, some readers will expect me to dwell on the energy question. It's the most visible constraint, the one that makes headlines. And Ireland offers a particularly stark example of the collision between AI ambition and climate reality.

In 2015, data centres consumed 5% of Ireland's metered electricity. By 2023, that figure had reached 21%. By 2024, it was 22%—more than urban households (18%) and rural households (10%) combined.18 Data centres in this small country now use more power than all the homes in Dublin. The International Energy Agency projects that figure will reach approximately 32%—a third of the national grid—by 2026.19

Here's the problem: Ireland is legally bound under the Climate Act 2021 to cut greenhouse gas emissions by 51% by 2030. The EU's Effort Sharing Regulation requires a 42% cut. In May 2025, the Environmental Protection Agency published its projections: Ireland will achieve, at best, a 22-23% reduction.20 Less than half the target. The first carbon budget has already been exceeded. The second will be exceeded by a wide margin.

This is the context in which data centre demand is set to consume a third of the national grid by 2026. On an island whose electricity infrastructure is already constrained—there's been a moratorium on new data centre connections in Dublin until 2028—in a country that will miss its legally binding climate targets by a country mile.

Globally, the trajectory is similar. The IEA estimates that data centres consumed around 415 terawatt-hours in 2024, roughly 1.5% of global electricity. Under their base case, that doubles to 945 TWh by 2030—equivalent to Japan's entire annual consumption. Under higher-growth scenarios, it exceeds 1,000 TWh.21

The infrastructure to support this doesn't exist yet. As one utility executive told CNBC: "We really don't have the electrical infrastructure to meet the aggressive targets. We don't have enough generation or transmission infrastructure to meet even the modest midpoint targets."22 Deloitte has documented 50,000-acre data centre campuses in early planning phases, each potentially requiring 5 gigawatts—the power demand of five million homes.23

And the environmental cost isn't just about electricity. Goldman Sachs estimates that roughly 60% of the new power for data centres over the next decade will come from burning fossil fuels, adding approximately 220 million tonnes of CO₂ to global emissions.24 A Cornell study published in Nature Sustainability found that US AI infrastructure alone could add 24 to 44 million tonnes of CO₂ annually by 2030—the equivalent of putting 5 to 10 million extra cars on the road.25 The water footprint is equally staggering: 731 to 1,125 million cubic metres annually, roughly equivalent to the world's entire consumption of bottled water.

Data centres are one of the few sectors where emissions are growing while most others are working to decarbonise. The IEA notes they're on track to join road transport and aviation as the exceptions to the global clean energy transition.

This is a real constraint. But here's the thing: it's a known constraint.

Engineers know how to build power plants. They know how to lay transmission lines. The obstacles are political, financial, and temporal, not conceptual. Given enough money and regulatory will, the grid can be expanded. It's expensive and slow, but it's a solved problem in principle.

The problems I've outlined—model collapse, the dead internet, cognitive atrophy—are different. They're not engineering challenges with known solutions. They're emergent pathologies, feedback loops that compound quietly until the damage is done.

The energy problem will dominate headlines. But it may be the least dangerous of AI's hidden costs, precisely because it's the one we can see.

The Counter-Move: Human First, AI Second

So what do we do?

I'm not an AI denialist. I've written elsewhere about the genuine utility of these tools: summarization, translation, brainstorming, coding assistance. The danger isn't the technology itself. It's the assumption that convenience comes without cost.

The key is sequence. Human first, AI second.

Here's what that looks like in practice:

Form your own thoughts before you ask for help. The generation effect isn't just a quirk of memory research; it's the mechanism by which understanding consolidates. If you outsource the first draft, you outsource the thinking. Write your outline before you prompt the model. Struggle with the structure before you ask for suggestions. The struggle is the work.

Treat AI as a brainstorming partner, not an oracle. The technology is good at generating possibilities, terrible at judgment. It will confidently tell you the clocks in Ireland go back in March and forward in October—the exact opposite of the truth—with utter conviction. It will cite sources that don't exist. It reads images at roughly a B-minus level: impressive enough to identify a Ford Transit in a rainy Irish car park, confident enough to misidentify the licence plates as British. It can translate Li Po's Chinese into something that parses as English, but compare the output to Ezra Pound and you'll see what's missing. Verify everything.

Protect your data. The free tiers of ChatGPT, Claude, and Copilot harvest everything you give them for further training. Google's consumer AI services offer no opt-out at all. If you're working with anything sensitive, pay for services with genuine privacy controls, or use local models. Understand what you're trading for convenience.

Value human-generated sources. Pre-2023 web content, produced before the slop flood, is increasingly precious. Seek out primary sources. Prefer libraries to search engines. When you find a human writer whose judgment you trust, bookmark them.

Practise the skills you want to keep. Navigate without GPS occasionally. Do arithmetic in your head. Write the difficult email yourself before you ask for a rewrite. The London taxi drivers didn't get larger hippocampi by thinking about navigation. They got them by doing it, repeatedly, under difficulty.

None of this requires abandoning the technology. It requires treating it as a tool rather than a crutch—amplification rather than replacement.

Conclusion: The Paradox of the Golden Age

The infrastructure bulls are probably right. This is not dot-com 2.0. The chips are running, the demand is real, the earnings exist. Powell wasn't wrong to distinguish this moment from the sock-puppet era.

But they're answering the wrong question.

The fragility isn't in the hardware. It's in the data: model collapse erasing the tails of human knowledge. It's in the web: flooded with slop until even the platform founders can't tell humans from bots. It's in the users: skills atrophying with every task outsourced, every struggle avoided, every difficult thought delegated.

We may be in a golden age that is sowing the seeds of its own destruction—not through idle capacity or financial speculation, but through contaminated inputs and eroded capabilities. The infrastructure holds while everything it's meant to process degrades.

The cost of answers is dropping to zero. The value of the question—the human question, the one only you can ask—becomes everything.

And the race to "AGI"? That infamously undefined Computer God that venture capitalists invoke like a prosperity gospel? It's laughable in light of all this. No matter how many chips you stack, no matter how many terawatts you throw at the problem, for large language models at least, we may be approaching the end of the line. Training on your own outputs doesn't lead to transcendence. It leads to intellectual mad cow disease.

My French Bulldog, the real one, knows nothing of probability distributions. He doesn't confuse church steeples with melted wax or cobblestones with scales. He knows what he sees. That's worth more than it used to be.

Make the most of this technology. It's a genuine leap forward, and we may not see its like again soon. But don't expect Moore's Law to apply here.26 And don't wait for AI God to save us.

The saving, as always, will have to be done by humans. While we still remember how.

Footnotes

Shumailov, I., Shumaylov, Z., Zhao, Y., Papernot, N., Anderson, R., & Gal, Y. (2024). AI models collapse when trained on recursively generated data. Nature, 631, 755–759. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07566-y

Powell, J. (October 2025). Federal Reserve Press Conference. Reported in Fortune, https://fortune.com/2025/10/29/powell-says-ai-is-not-a-bubble-unlike-dot-com-federal-reserve-interest-rates/

International Energy Agency. (April 2025). Energy and AI. https://www.iea.org/reports/energy-and-ai

Janus Henderson Investors. (December 2025). "Riding the AI wave: How can tech investors harness change and volatility?" https://www.janushenderson.com/corporate/article/riding-the-ai-wave-how-can-tech-investors-harness-change-and-volatility/

Nadella, S. (January 2025). X/Twitter post. https://x.com/satyanadella/status/1883753899255046301

IBM, Wikipedia, and various industry commentators have used these colloquial terms. See also coverage in Nature News: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-024-02420-7

Dohmatob, E., Feng, Y., & Kempe, J. (2024). A Tale of Tails: Model Collapse as a Change of Scaling Laws. Proceedings of the 41st International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML 2024).

Imperva. (2024). 2024 Bad Bot Report. Thales Group. The report found 49.6% bot traffic in 2023, with bad bots comprising 32% of all traffic. https://www.imperva.com/resources/resource-library/reports/2024-bad-bot-report/

Imperva. (2025). 2025 Bad Bot Report. Thales Group. For the first time in a decade, automated traffic surpassed human-generated traffic, constituting 51% of all web traffic in 2024. https://www.imperva.com/resources/resource-library/reports/2025-bad-bot-report/

Ahrefs. (2025). "74% of New Webpages Include AI Content (Study of 900k Pages)." https://ahrefs.com/blog/what-percentage-of-new-content-is-ai-generated/

Altman, S. (September 2025). X/Twitter post. Reported widely including Fortune, TechCrunch, and TIME. https://fortune.com/2025/09/09/sam-altman-people-starting-to-talk-like-ai-feel-very-fake/

Ohanian, A. (October 2025). Interview on TBPN podcast. Reported in Fortune. https://fortune.com/2025/10/15/reddit-co-founder-alexis-ohanian-dead-internet-theory-ai-bots-linkedin-slop/

Maguire, E. A., Gadian, D. G., Johnsrude, I. S., Good, C. D., Ashburner, J., Frackowiak, R. S. J., & Frith, C. D. (2000). Navigation-related structural change in the hippocampi of taxi drivers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 97(8), 4398–4403. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.070039597

Budzyń, K., Romańczyk, M., Kitala, D., et al. (2025). Endoscopist deskilling risk after exposure to artificial intelligence in colonoscopy: a multicentre, observational study. The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 10, 896–903. The study found clinicians became "less motivated, less focused, and less responsible" when making cognitive decisions without AI assistance after approximately six months of AI use. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/langas/article/PIIS2468-1253(25)00133-5/fulltext

van Nimwegen, C. (2008). The paradox of the guided user: assistance can be counter-effective (Doctoral dissertation). Utrecht University. https://dspace.library.uu.nl/handle/1874/26875

Slamecka, N. J., & Graf, P. (1978). The generation effect: Delineation of a phenomenon. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Learning and Memory, 4(6), 592–604.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1934/1962). Thought and Language. MIT Press.

Central Statistics Office Ireland. (2024, 2025). Data Centres Metered Electricity Consumption. Data centres consumed 21% of metered electricity in 2023, rising to 22% in 2024, compared to 5% in 2015. https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/ep/p-dcmec/datacentresmeteredelectricityconsumption2024/

International Energy Agency. (January 2024). Electricity 2024 – Analysis and forecast to 2026. The IEA projected data centre demand in Ireland could reach approximately 32% of total electricity demand by 2026.

Environmental Protection Agency Ireland. (May 2025). Greenhouse Gas Emissions Projections 2024-2055. Ireland is projected to achieve a reduction of up to 23% in total greenhouse gas emissions by 2030, compared to a national target of 51%. The first carbon budget is projected to be exceeded by 8-12 Mt CO₂eq; the second by 77-114 Mt CO₂eq. https://www.epa.ie/news-releases/news-releases-2025/epa-projections-show-ireland-off-track-for-2030-climate-targets.php

International Energy Agency. (April 2025). Energy and AI. Global data centre electricity consumption estimated at 415 TWh in 2024 (1.5% of global consumption), projected to reach 945 TWh by 2030 under the base case, exceeding 1,000 TWh under higher-growth scenarios. https://www.iea.org/reports/energy-and-ai

CNBC. (2025). Interview with utility executives on AI infrastructure demands. Multiple sources report similar constraints on generation and transmission capacity.

Deloitte. (June 2025). Analysis of data centre development pipelines, noting 50,000-acre campuses in early-stage planning with potential 5 GW demand.

Goldman Sachs Research. (August 2025). Analysis of data centre power sources, forecasting that approximately 60% of increasing electricity demands from data centres will be met by burning fossil fuels, increasing global carbon emissions by approximately 220 million tonnes.

You, F., et al. (2025). Environmental impact and net-zero pathways for sustainable artificial intelligence servers in the USA. Nature Sustainability. The study found US AI infrastructure could generate 24-44 million tonnes CO₂-equivalent annually by 2030, with a water footprint of 731-1,125 million cubic metres. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41893-025-01681-y

Moore's Law—the observation that transistor density doubles approximately every two years—has driven exponential growth in computing power since the 1960s. However, AI capability improvements depend not just on compute but on training data quality, a resource that may be degrading rather than expanding. The law describes hardware; intelligence requires something more.