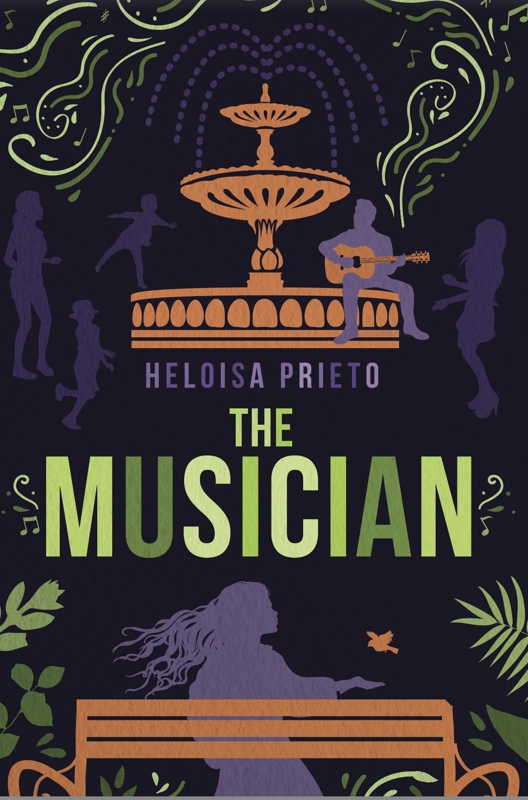

Thomas is a young musician of extraordinary gifts—orphaned young, wealthy but isolated, accompanied since childhood by "secret creatures of sound" that only he can see and hear. Heloisa Prieto's The Musician follows him into danger and back out again, though not by the route you'd expect.

The novel reads like a fable, almost like something told aloud around a fire, but beneath that apparent simplicity is genuine craft. The chapters are brief—some only a page or two—and they create a rhythm that pulls you forward without rushing. Prieto's prose has a musicality to it, which feels appropriate given the subject matter. It moves the way Thomas's music does: quietly, then with sudden swells of intensity, then quiet again.

The plot I'll leave mostly undisturbed for you to discover. What I can say is this: Thomas plays his guitar in a public square in São Paulo. Strangers gather. Some are drawn to protect him; others want something from him—his talent, his attention, his soul in the old mythic sense. The novel asks what it means to belong somewhere, and whether belonging can become a trap. It asks who gets to own beauty, and whether that question even makes sense. At one point, an elder puts it simply: "Does the sun belong to you? Do the stars belong to you?" The question isn't rhetorical. It's a genuine reframing—one the whole book has been building toward.

What moved me most was the found-family element. The people who come to matter in Thomas's life aren't connected to him by blood or obligation. They're strangers who recognize something worth protecting and choose to act. A scriptwriter and her husband. Their two small boys, who seem to perceive things adults have forgotten how to see. An academic who's spent her life distrusting intuition. A young Guarani woman named Marlui, whose presence in the novel is one of its great gifts.

As a gay man, I found this architecture deeply familiar. The "found family" is a cornerstone of LGBTQ+ culture—those of us who've lived on the margins of conventional belonging know what it means to build kinship from scratch, to look at near-strangers and say I see you, I'll stand with you. Prieto doesn't make this connection explicitly; Thomas isn't coded as queer, and the novel doesn't gesture toward it. But the emotional shape is the same. The people who matter aren't bound by duty. They simply show up. That felt true to me in a way that transcended the specific story.

Equally striking is how Prieto handles her Guarani characters. Marlui could so easily have been a mystical prop—the wise Indigenous woman who exists to heal the troubled Westerner and then recede into the scenery. She isn't. She has opinions. She pushes back. When a city-dwelling character makes assumptions about "forest people" and technology, Marlui doesn't let it slide. She points out that daily bathing, ecological knowledge, the very fruits urban Brazilians take for granted—these came from Indigenous traditions. "Our culture is rich and healthy," she says, "but it has been recorded orally, from mouth to ear, and all you seem to value is the printed word." It's not a lecture; it's a lived perspective, delivered by a character who feels fully present rather than symbolic.

Her grandfather Popygua is similarly grounded. He's a healer, yes, and his spiritual practices are presented as genuinely real within the novel's logic. But he's also a man with limits, protocols, and a dry sense of humour. He doesn't exist to validate Thomas or to dispense wisdom on demand. When Thomas, eager to contribute, asks to participate in something he hasn't earned, Popygua simply says no. "Just listen, my boy. You must listen again." It's not mysticism for export. It's a living tradition, and Thomas—like the reader—must come to it with humility.

There's a small moment I keep returning to. Thomas, visiting the village, challenges some children to a swimming race. They decline. "Kids here don't like competing," Marlui explains. They're taught to wait for the slower ones. It's barely a page, easy to skim past, but it quietly inverts so many assumptions about achievement, excellence, and worth. The book is full of these small inversions—moments where what seems obvious is gently turned over and revealed to be merely habitual.

I should say something about magical realism, because The Musician sits firmly in that tradition, and as a reader raised on Western literary conventions, it asked something of me. The "secret creatures of sound" are never explained or rationalized. Characters perceive things across distances. Visions arrive and are acted upon. You either accept the premise or you don't—and accepting it means loosening your grip on what counts as "real."

I found this liberating rather than frustrating. Magical realism, at its best, isn't asking you to believe in literal magic. It's asking you to consider that the empirical frameworks we've inherited might not be the only valid ways of knowing. That other cultures, other traditions, might have access to truths that our insistence on the measurable has cost us. Prieto never preaches this. The magic simply is, woven into the fabric of the story as naturally as the music Thomas plays. You move through it as Thomas does—uncertain at first, then grateful for the expanded territory.

There's a generosity to this book. Generosity toward its characters, who are allowed to be flawed and uncertain. Generosity toward its readers, who are trusted to keep up without having everything explained. Generosity toward traditions—both the European mythic inheritance (Orpheus haunts these pages, though not in the way you might expect) and the Indigenous Brazilian wisdom that Prieto has spent decades learning from and advocating for.

Who should read The Musician? Anyone who loves music and has ever wondered where it really comes from. Anyone who's felt the pull of belonging somewhere that wanted too much in return. Anyone who's built a family from choice rather than circumstance and knows what that costs and what it gives. Anyone willing to let a story ask questions rather than answer them.

Some songs stay with you long after the last note.