I'll be honest: when I started This Way Out, I had a fear I was about to wade into a tale of endless tragedy and cruelty to children. The opening chant the boys sing—"Papa's dead and Mama's gone / Now we call this joint our home"—didn't exactly settle my nerves. Thankfully, I was wrong about what lay ahead.

Yes, there's tragedy here, and cruelty. But there's also joy and triumph, brotherhood and friendship—the full spectrum of life. In the end it was a joy to read, even when there were moments that brought a tear to my eye.

The novel follows a group of boys growing up in The Dumonde College for Boys, an all-White orphanage in North Philadelphia, from the late 1950s through the civil rights era. At its heart are three friends—Mickey, Jack, and Alex—who arrive together as seven-year-olds after their fathers die in a single car crash. The newspapers called it "The Woodstock Street Tragedy." The boys call themselves The Car-Crash Kids.

One line, delivered during a rapid-fire exchange between the boys, feels like the novel's thesis: "We didn't grow up in the world. The world grew around us." It captures something I haven't seen articulated elsewhere—the particular dislocation of institutional childhood. Not deprivation exactly, but displacement. The world happens elsewhere, and these boys watch it grow around them like a tree growing around a fence post—incorporating them without including them.

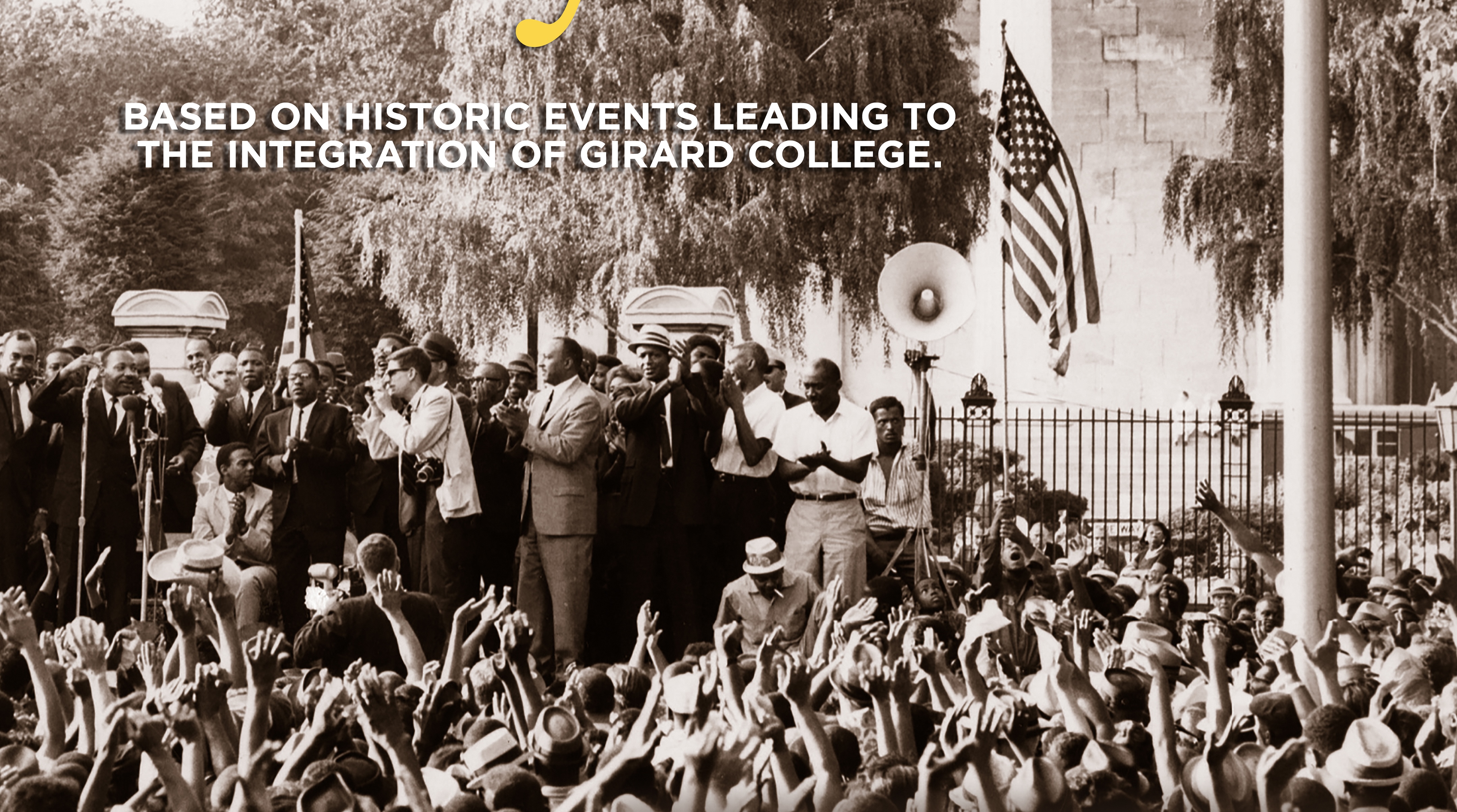

The wall looms large, literal and metaphorical. One passage puts the effect of segregation into sharp relief: "We watch Black kids across the wall. They watch us. We worry them. They worry us. We're afraid of them. They're afraid of us. We're learning how to hate." Children are not born hating—they learn it. The architecture of segregation becomes the pedagogy of hatred. So much packed into this snippet: mutual fear, mutual ignorance, mutual diminishment. Neither side chose this. The wall taught them.

The novel builds its case methodically. Henri Dumonde, the nineteenth-century founder, emerges as a complicated figure: philanthropist, benefactor, slave trader, opium profiteer. His journals, recorded by Hélène Labelle—his enslaved African secretary and mistress—reveal the contradictions at the heart of American benevolence. Patrick Henry's "Give me liberty or give me death" sits against his admission that he "cannot imagine the general inconvenience of living without slaves." And then Voltaire, whom Dumonde revered: "The comfort of the rich depends upon an abundant supply of the poor." At least Voltaire named it honestly. The novel refuses to resolve these contradictions—it simply holds them up to the light.

Roger McCullough arrives at Dumonde like a force of nature: a hulking former NFL player with a steel prosthetic thumb, a Spanish bullwhip, and a battered Land Rover caked in mud from his years as a field geologist. He becomes the boys' guardian angel, their Better Angel—the adult who sees them as worth saving. Roger says something that becomes the novel's theory of fatherlessness: "A boy cannot understand himself unless he knows his father. Good. Bad. Dead or alive." It's not absence but epistemological crisis. The Car-Crash Kids can't fully know themselves because the knowledge that would anchor them died on Woodstock Street.

And then there's Daisy Walker, the Black neighbour who befriends the boys across the wall, playing spy poker through binoculars, lowering baskets of food to her son. Her rejoinder to Roger—"No matter how old you are, you are still just a stupid boy"—isn't deflation. It's tenderness. She's telling him the wound doesn't heal, but the wound doesn't define him either.

One storyline stayed with me for days. Early in their time at Dumonde, Mickey nearly kills another boy, Raymond, in a moment of blind rage. Raymond forgives him. They become friends. But friendship and forgiveness have limits; guilt does not. Once done, no act can be undone—and consequences have a way of confirming our worst fears about ourselves. The novel's verdict: "What if? is a foolish dream. There is only What now? And What next? And the better question, How to forgive yourself?" The novel doesn't resolve this. It lets Mickey carry it.

The structure is testimonial—rapid exchanges, overlapping voices, vignettes that accrete into a larger picture. The novel trusts its readers to draw conclusions rather than spelling them out. Good storytelling, in other words. Show, don't tell.

What struck me most was how prescient the writing feels. For a novel set sixty-odd years ago, it speaks directly to now: the architecture of segregation, the pedagogy of hatred, the contradictions of philanthropy built on exploitation. These aren't historical artefacts. They're ongoing.

I found myself becoming emotionally invested in these lads, rejoicing in their triumphs and grieving their losses. There are victories here—moments when the boys find their voice and force a reckoning with the adults who failed them. There are also losses I didn't see coming, losses that winded me. These weren't narrative events. They were personal.

The novel does what the best testimony does: it makes the reader a witness. I can't unknow what I now know about Dumonde, about these boys, about the griefs they carry and the joys they steal. It's a book I'll be carrying with me for a long while yet.